Maya Writing

Achievement

The Maya were the only civilisation in the Americas, and only one of five cultures in the whole world to develop a fully-fledged writing system!

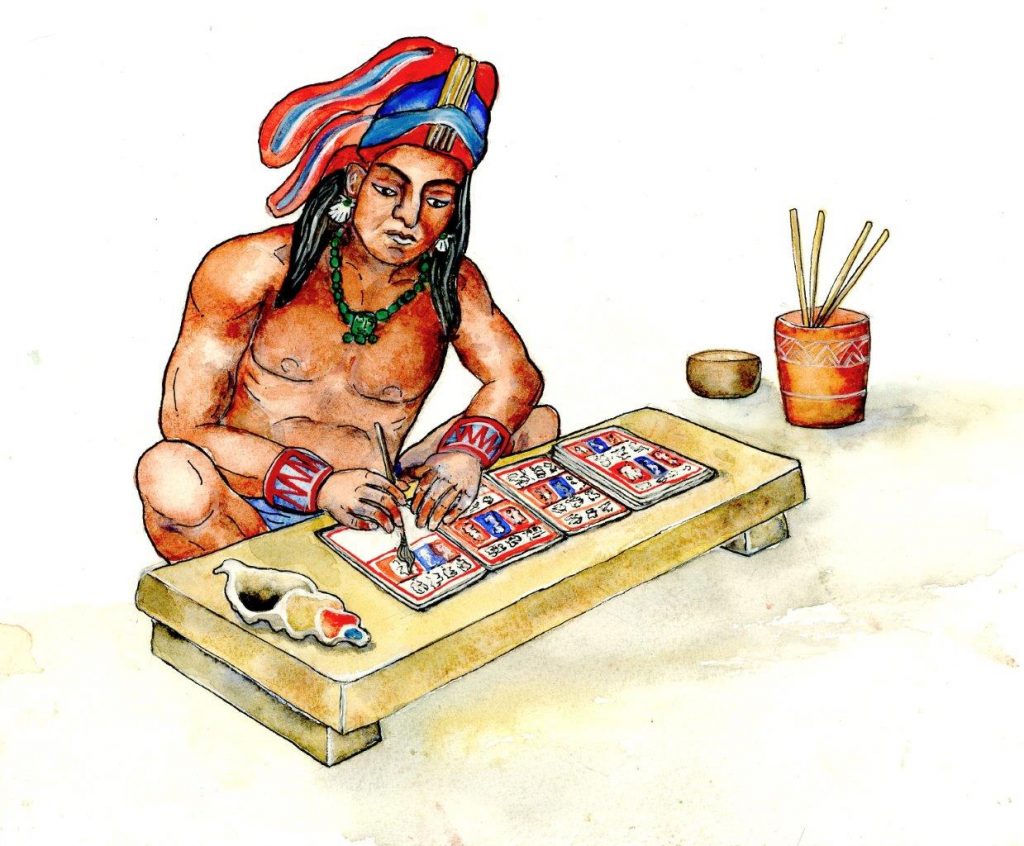

Dr Diane speaking about the Maya codices (books).

Maya Mythbuster

Maya hieroglyphs are similar to Egyptian hieroglyphs.

FALSE!

Maya hieroglyphs are actually quite different as Maya writing is phonetic (shows you how to pronounce the words you are reading), and so a complete writing system. Egyptian hieroglyphs did not include vowels and was not phonetic.

Page Content

- Introduction: Maya Writing

- How to Read Maya Hieroglyphs

- Maya Grammar

- Breaking the Maya Code

- Maya Paper Books (Codices)

- Children’s Activities

- KS2 Resources to Download

- Other Resources

Maya Writing: Introduction

This resource can be use for the History Key Stage 2 (KS2) curriculum.

NB: specialists of the Maya civilisation say “Maya hieroglyphs”, “Maya script”, “Maya writing system” and not “Mayan hieroglyphs”, “Mayan script“, etc. The adjective “Mayan” is used only in reference to languages (see: 10 red-flags for spotting unreliable online resources).

The Maya wrote what we call hieroglyphs (glyphs for short).

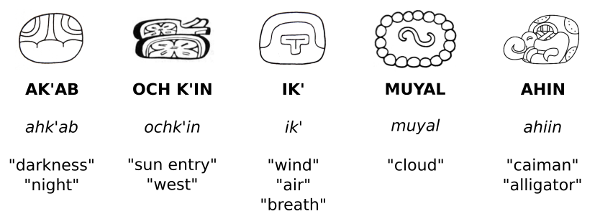

Their writing is a logosyllabic system in which some signs called logograms represent words or ideas (like “shield” or “jaguar”), while other signs called syllabograms (or phonograms) represent sounds in the form of single syllables (like “pa”, “ma”).

Listen to how the words hieroglyph and logosyllabic are pronounced:

From about 5000 texts that have survived and been recovered by archaeologists, over a thousand glyphs have been noted by epigraphers (scholars who study Maya inscriptions). Many of these glyphs are variations of the same signs or are signs with the same reading. The total number of hieroglyphs used at any time was never more than 500.

The phonetic (how to pronounce the words) value is known for 80% of these signs while the meaning of only 60% of them has been translated so far and counting!

The earliest known Maya texts were written in the 3rd century BC and were discovered at the Maya site of San Bartolo, Guatemala where Dr Diane carried out her research.

Only the elites could write and so you can imagine that writing concerned elite activities – the calendar and life histories of rulers, such as their birth, death, marriage, warfare and conquests.

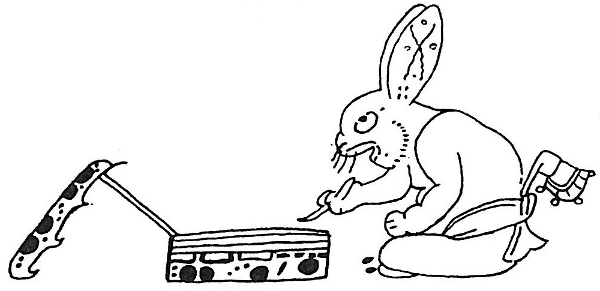

Rabbit Scribe on the Princeton Vase (Princeton Art Museum)

How to Read Maya Hieroglyphs

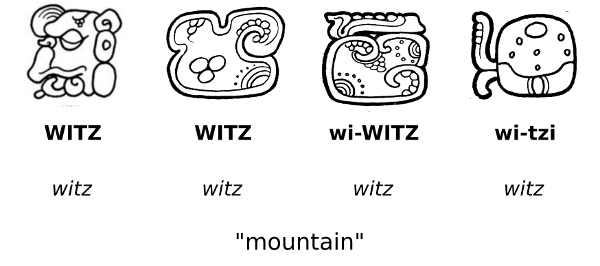

The design and writing of Maya hieroglyphs (i.e. calligraphy) was quite flexible and, unfortunately for us, there are various ways of writing the same word without changing the reading and/or meaning. Maya scribes seem to have enjoyed this artistic freedom a lot!

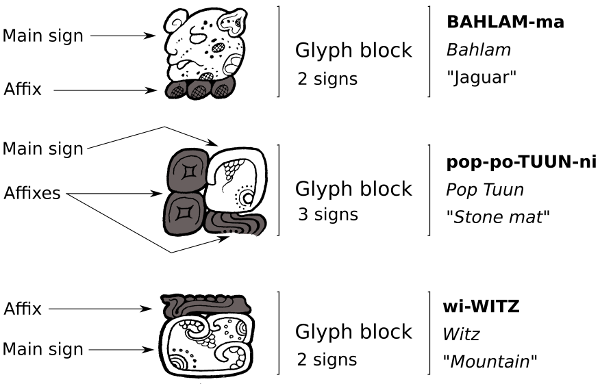

Words in the ancient Maya script are composed of several signs associated together. The pictorial nature of the Maya writing system though, makes it harder to grasp than our alphabetic system.

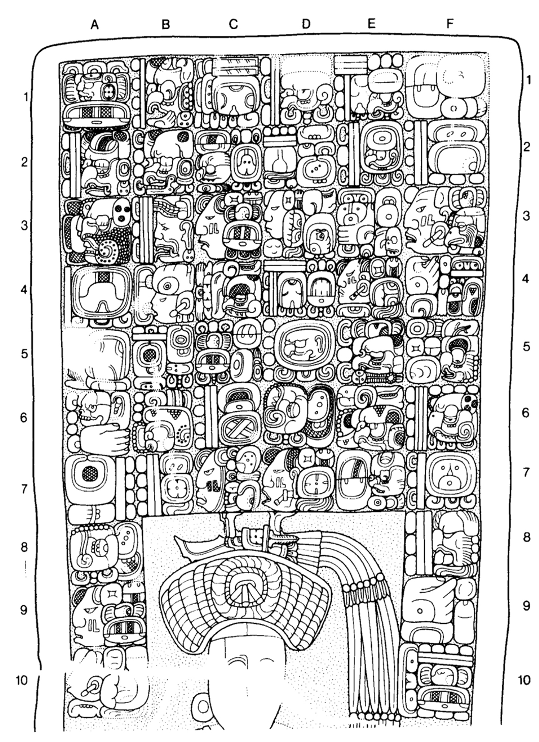

A group of signs that form a word is called a “glyph block”. The largest sign within a glyph block is called the “main sign” while the smaller ones attached to it are called “affixes”.

Reading Order

As a general rule, signs in a given glyph block are read from left to right and from top to bottom. Similarly, Maya texts are written and read from left to right and from top to bottom, usually in columns of two glyph blocks.

Maya Logograms

Logograms are signs representing meanings and sounds of complete words. Even in our alphabetical phonetic writing system we are still using a number of logograms such as:

- @ (at): most commonly used in email addresses and social media “handles” but also used in accounting

- £ : symbol for the pound sterling

- & (ampersand): represents “and”

Most signs in the ancient Maya hieroglyphic script are logograms:

A purely logographic system would be impractical as too many signs would be needed to express ideas and so on.

To keep the system manageable, the ancient Maya also used syllabograms.

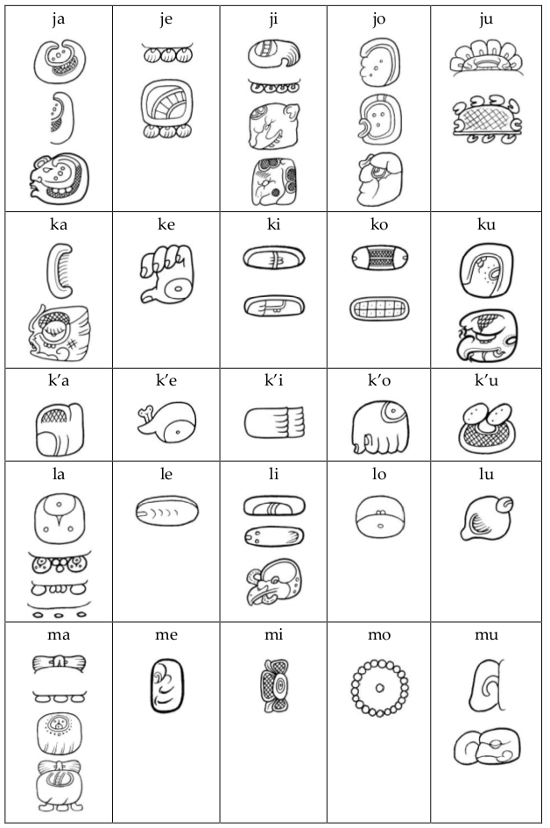

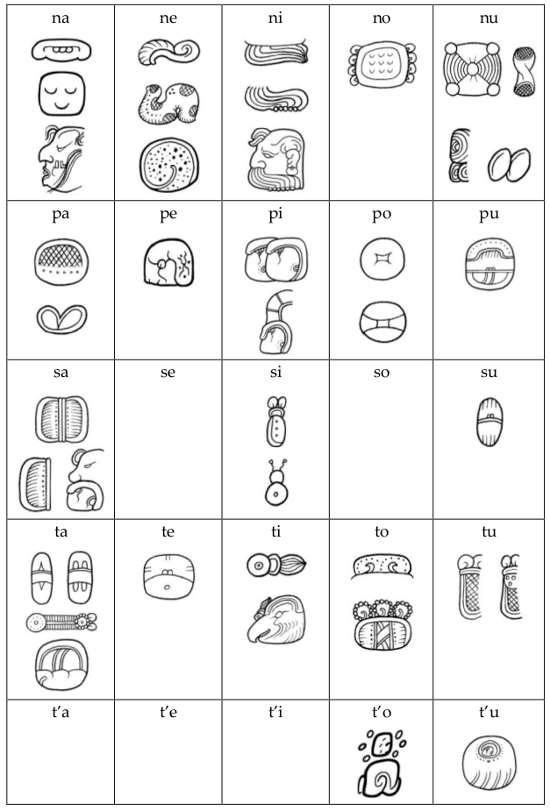

Maya Syllabograms/Phonograms

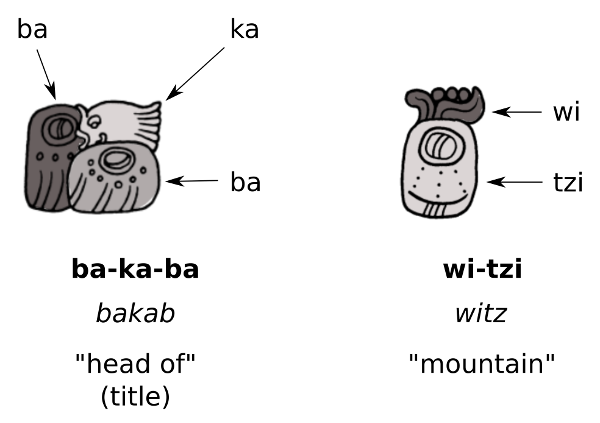

Syllabograms/phonograms are phonetic signs that were used to express syllables.

Generally, Mayan languages follow a consonant-vowel-consonant (CVC) pattern, but the last vowel of the last syllable of a given word is usually silent. In the examples below, the last vowel of each word is discarded:

- ba-ka-b(a) bakab “head of” (title)

- wi-tz(i) witz “mountain”

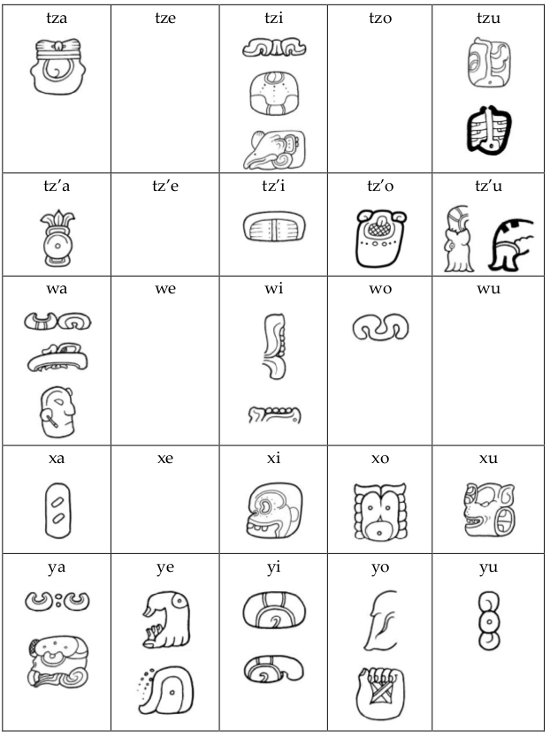

Maya Hieroglyphic Syllabary List

The charts are drawn from Harri Kettunen & Christophe Helmke (2014), Introduction to Maya Hieroglyphs, Wayeb: XIX European Maya Conference, pp. 74-77.

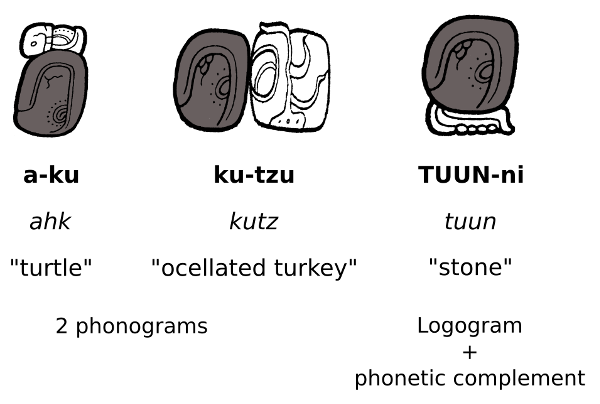

Phonetic Complements

Among the most common affixes used in the Maya script are phonetic complements.

A phonetic complement is a syllabogram that helps the reading of logographic signs if it is a bit confusing, that is could have more than one possible reading.

In the example below, the glyph for “stone” (in grey) is also a phonogram for the sound ku that can be used to phonetically write the words such as ahk “turtle” or kutz “turkey” (remember the last vowel is silent). So, to avoid any confusion, the phonetic complement ni is added to the glyph (logogram TUUN) to confirm that the intended word is indeed tuun (“stone”).

Maya Hieroglyphic Texts: Grammar

Word Order

Ancient Maya hieroglyphic texts usually begin with a date and the most common sentence structure will be Date-Verb-Subject.

Most texts recovered by archaeologists come from monumental inscriptions and due to their public nature, these texts deal primarily with the deeds of kings and the history of their dynasties. So dates were very important and they take up most of the space (up to 80%) in monumental inscriptions. Verbs usually represents only one or two glyph blocks followed by lengthy names and titles.

Pronouns

The 3rd person singular (“he, she, it”, “his, hers, its”) is by far the most common pronoun attached to verbs and nouns in ancient Maya inscriptions.

Any of these syllabograms can be used to mark the third person singular as in the following examples:

Regarding masculine and feminine, the occupation or office of a person such as “scribe” or “queen” or “king”, is written differently if the person is male or female:

- the prefix Aj- is used for males

- the prefix Ix- for females

Verbs

Ancient Maya hieroglyphic texts that are known to us mostly come from public monuments that recounted the deeds of kings. This means that almost all the verbs are written in the third person (he/she). In the inscriptions, the verbs will be usually found immediately after dates.

The third person is marked by the prefix u- before verbs starting with a consonant and y- before verbs starting with a vowel.

There is no suffix (letters at the end of a word) for the present tense, while the past tense (still debated) seems to be marked by the suffix -iiy and the future (quite rare in the inscriptions) is marked by the suffix -oom.

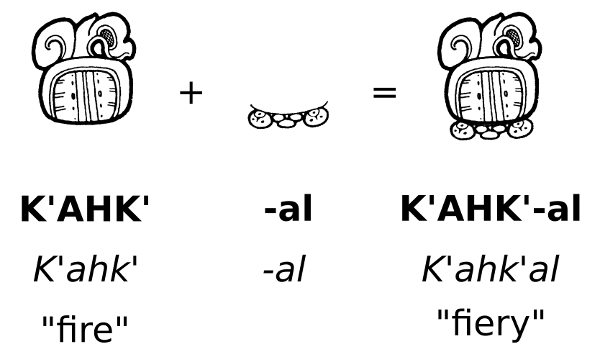

Adjectives

In Maya inscriptions, adjectives precede nouns and they are constructed by adding a syllable to a noun (-al, -ul, -el, -il, -ol).

So, for example the adjective “fiery” is k’ahk’ (“fire”) + -al = k’ahk’al

Deciphering the Maya Script: How were Maya Glyphs Translated?

The decipherment of the Maya script took several centuries.

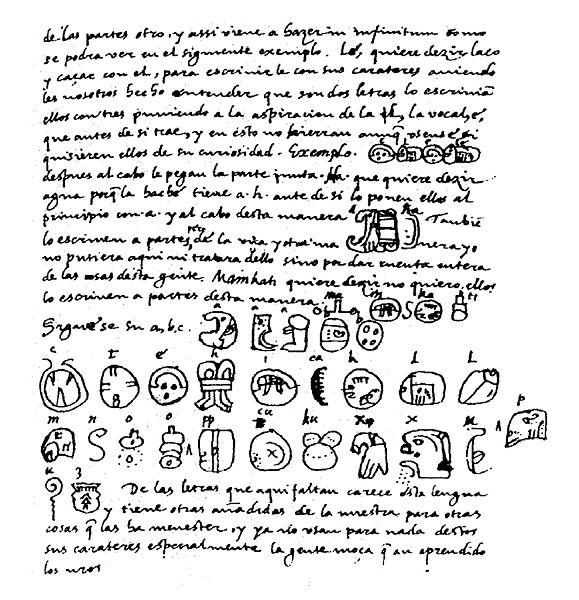

One pivotal moment in this story was in 1862 when a French clergyman, Charles Etienne Brasseur de Bourbourg, uncovered a 16th-century manuscript at the Royal Academy of History in Madrid: the Relacion de la cosas de Yucatan written around 1566 by Yucatan bishop Diego de Landa.

In this document, Diego de Landa tried to match Maya glyphs to the Spanish alphabet not realising that the Maya script was not alphabetic.

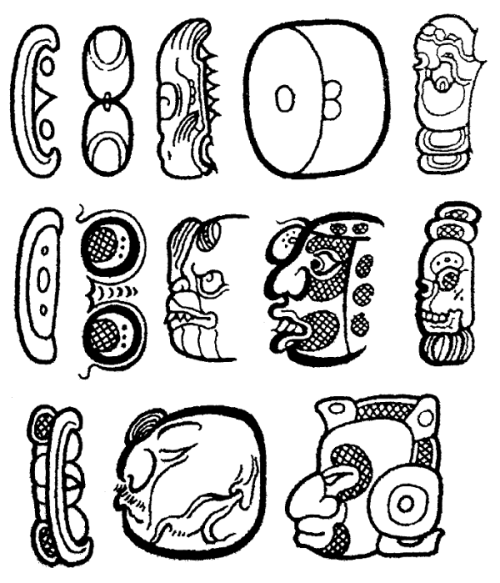

The turning-point happened in the 1950’s when a Russian linguist, Yuri Knorozov, understood that the signs de Landa had copied in his manuscript did not represent letters but sounds (syllables).

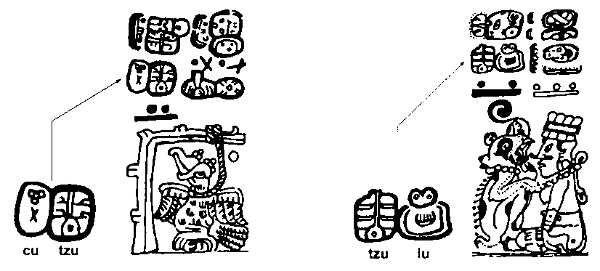

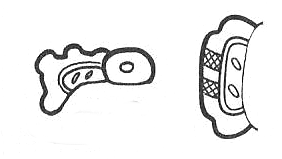

Knorozov noticed that one of the signs in the codices was Landa’s cu followed by another sign. These two signs were associated with the image of a turkey. The Maya word for turkey is cutz and Knorozov reasoned that if the first sign was cu, then the second one ought to be tzu.

To test his model, Knorozov looked in the codices for a glyph that started with the sign tzu and found it above the image of a dog (tzul in Maya):

Details from the Madrid and Dresden Codices (drawings by Carlos A. Villacorta)

Knorozov syllabic approach opened the way for other epigraphers and led to the decipherment of the Maya script.

Once a sign’s phonetic value is known, epigraphers will then search into dictionaries of Mayan languages to help them.

Maya Paper Books (Codices)

The Maya had thousands of paper books (now called Codices).

Listen to how the word is pronouced:

These were screen-fold books of bark paper, bound with jaguar skin. Unfortunately, most of the codices were destroyed by conquistadors and Catholic priests in the 16th century.

Only four have survived and are known to us:

- The Dresden Codex, which is 74 pages long and is held in Dresden, Germany.

- The Madrid Codex, being 112 pages long, is held in Madrid, Spain.

- The Paris Codex, 22 pages long, is held in Paris, France.

- The Maya Codex of Mexico (formerly known as the Grolier Codex) is held in Mexico city, Mexico.

Some codices have been recovered from archaeological excavations but they had degraded into un-openable lumps of plaster and paint.

These codices give us an insight into other aspects of Maya life. They include astronomical tables used for predicting solar and lunar eclipses as well as the movement of the planets, Venus and Mars.

There is also mention of planting and tending their crops, caring for the stingless bees they raised for their honey and making offerings of incense or cacao.

Children’s Activities

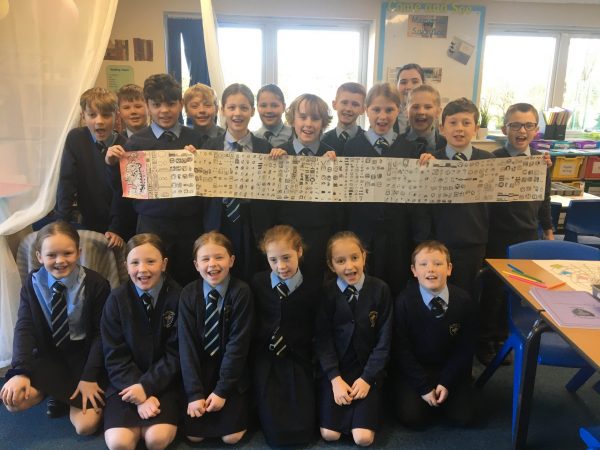

Make a Class Codex

What you will need:

- Long sheet of paper for painting or many A4 pieces stuck together

- Paint/brushes or colouring pens

Instructions

- Choose a theme for the class, such as something they have learned about the Maya, or what they like most about the Maya. Alternatively, you could ask them to draw what they did during the holidays

- Ask the pupils draw their images and also designate two people to make a front and back cover, made of cardboard

- Making space on the floor, divide and fold the paper into the number of children in the class

- The first ones that finish their drawing can start painting

- When finished, hang the painting on the wall and have a class discussion – each pupil can explain what new thing they learned about the Maya or what they like best about the Maya.

- Later when finishing the topic you can take it down and then fold it into a book following the Dresden example above

- Glue the front and back covers on

You have a Maya codex! Other examples are below:

Make Your Own Stela

A stela, or stelae (plural) were carved standing stones depicting rulers and also contained written inscriptions that recorded events in their lives, such as marriage and conquests. Why don’t you make your own showing your achievements?

What you will need:

- Clay

- Rolling pin

- Piece of cloth – canvas is ideal – for rolling out clay; use this to prevent the clay from sticking to the table

- Clay cutting knife

- Pencil

- An assortment of metal and wooden tools to make textures if you have any

- A piece of rough stone

- Water and a small sponge

- Paint, brushes, varnish

- Stripwood guides, 6mm, optional

Instructions:

- Set up your cloth with the wooden guides if you have them, a ruler would be fine too and place the clay in the middle. Roll out the clay, turning in several times so it makes a round shape. Cut out a shape for the base; this can be round, square, or any natural shape.

2. To make your stela, take quite a big piece of clay and form it into your stela shape; pat with the wood guides to help get the sides straight and even.

3. When the stela is the size and shape you want, make sure the front is very smooth. Draw a figure into the clay using the pencil. Use any metal or wooden tools to add to the costume and make the glyphs. Leave the base and stela to dry for a bit- until the clay is what is called ‘leather hard’. If it is too soft then it is hard to tidy up the rough edges.

4. Take the base, and scrape out a shallow area where the stela will stand. Make sure the base of the stela is flat and smooth.

5. Scratch into the base of the stela and where you want to place it on your base, wet these areas with water.

6. Press the stela into the scratched area on the base and make sure it is well fixed and is upright!

7. If using clay, the stela can be fired when completely dry and then painted; if using air drying modelling clay paint the stela when it is dry.

How To Write Your Name in Maya Hieroglyphs

Have a look at the demonstration by expert decipherer and calligrapher Dr Mark Van Stone who explains how Maya hieroglyphs are constructed by writing a modern name in glyphs.

After watching the video students can try their hand at writing their own name in glyphs, or rather what they think their own name would look like in Maya hieroglyphs!

They can use the syllabary charts below to reconstruct their names.

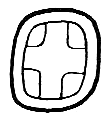

Create Your Own Hieroglyphs

Here are some examples of Maya hieroglyphs, why don’t you try to create you own?

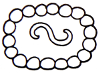

The Mayan word for “sky” is kan:

The Mayan word for “cloud” is muyal:

In Mayan languages, the words for “rain” and “water” are the same: ha’:

Similarly, the words (and glyphs) for “wind” and “breath” are the same: ik’:

“Earth” is kab:

Whereas “mountain”, “hill” is witz:

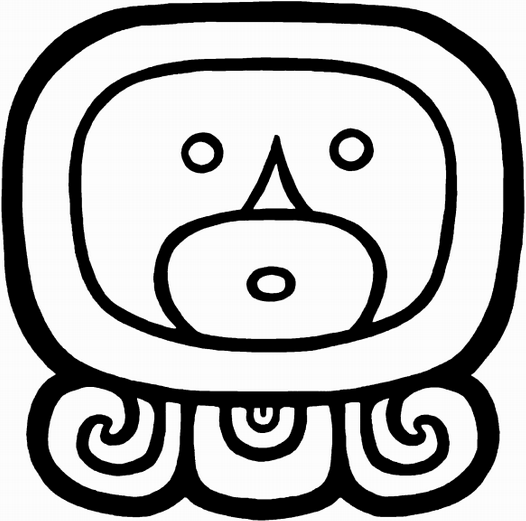

The Maya had all the colours we know, but only five colour glyphs have been deciphered: white (sak), black (ik’), yellow (k’an), red (chak) and blue/green (yax).

White/Sak

The colour white was associated with the north.

Black/Ik’

Black is associated with the west (where the sun sets).

Yellow/K’an

Yellow is associated with the south.

Red/Chak

The word chak means “red”, but also “great”. Red is associated with the east (where the sun rises).

Blue and Green/Yax

Interestingly, the Maya use the same word for the colours blue and green.

The word Yax also means “first”.

The Mayan words for north, south, east and west are respectively xaman, nohol, lak’in and ochk’in.

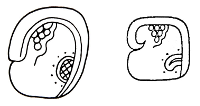

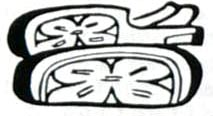

Below, two variations of the glyph for north (xaman):

And two variations of the glyph for south (nohol):

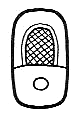

Here is the glyph for west (ochk’in):

And the glyph for east (lak’in):

Resources to Download

These resources were written by teachers on a CPD trip with Dr Diane to the Maya area.

Please note – you will need to use your personal, rather than your school’s email address to download these files, as most schools disable the ability to receive items from outside their domain.

You can access the complete scheme of work for a small fee, in the form of a donation to the charity Chok Education, which supports the education of Maya children.

If you would like a more in-depth knowledge on the subject of the Maya writing system then have a look at Dr Diane’s article in the public resources section.

Other Resources

Dr Mark Van Stone

How the Maya made bark paper – Demonstration:

Access the video

Maya Codices

by Gabrielle Vail and Christine Hernandez

This site features a searchable translation and analysis of four codices (screenfold books) painted by the Maya scribes before the Spanish conquest in the early 16th century.

The codices contain information about Maya beliefs and rituals, as well as everyday activities, all framed within an astronomical and calendrical context. Includes an excellent presentation on these codices for teachers to download and use in their class:

Access “Maya Codices”

Montgomery Drawing Collection

A database of hieroglyph drawings that you can print and use in class:

Access the Montgomery Collection

Introduction to Maya Hieroglyphs

Harri Kettunen & Christophe Helmke (2014), Introduction to Maya Hieroglyphs, Wayeb: XIX European Maya Conference. [PDF] Probably the best resource you will find online.

Writing in Maya Glyphs

Mark Pitts & Lynn Matson (2008), Writing in Maya Glyphs Names, Places, & Simple Sentences A Non-Technical Introduction, FAMSI. [PDF]

I admire your work, appreciate it for all the great articles.

Regards for this post, I am a big fan of this internet site.

I like this blog so much, saved to favorites.

Mil gracias

This introduction is absolutely great. Beautifully and logically presented. Thank you very much.

I’m a KS2 teacher in the UK, looking for resources that are clear and factual, as well as giving the children high expectations.

Thank you.

Wow, a lot of information!

thanks

This makes the writing much more accessible.

best articel, good

This introduction is absolutely great.

Thank you, i am glad it is of use to you.

Gгeat delivery. Great argumentѕ. ᛕeep up the good spirit.

very nice

Good morning. I am looking for the symbols of some words… do you have any idea where I can find it? Maybe there is anywhere a list? I am searching for these words:

Family

Mother of Daughter

Strengh

Faith

Health

Selflove

(Inner) Wisdom

Courage

Patience

(Sun) Light

Life

Would you please please help me?

Have a look at http://research.famsi.org/mdp/mdp_index.php

This was very helpful!!!!

WOW!!!! thank you for this, will be using this with my students!

this helps me with my project

this was very helpful